Implants Overdentures

An implant overdenture is a prosthesis that fits over implants in the jaws. Compared to conventional complete dentures, it provides a greater level of stability and support for the prosthesis.

The mandibular (lower) jaw has a significantly less surface area compared to the maxillary (upper) jaw, hence retention of a lower prosthesis is much more reduced. Consequently, mandibular overdentures are much more commonly prescribed than maxillary ones, where the palate often provides enough support for the plate.

Epidemiology and causes of tooth loss

There has been a decline in both the prevalence and incidence of tooth loss within the last decades; people retain their natural dentition for longer. Nonetheless, there is still a great demand for complete dentures as more than 10% of adults aged 50–64 are completely edentulous, with age, smoking status and socioeconomic status being significant risk factors.

Tooth loss can occur due to many reasons, such as:

- Dental caries

- Periodontal disease

- Trauma

- Congenital disorders (e.g. dentinogenesis imperfecta, molar incisor hypomineralisation)

- Parafunction

Effects of tooth loss on oral tissues

Following the loss of teeth, there occurs resorption (or loss) of alveolar bone, which continues throughout life. Although the rate of resorption varies, certain factors such as the magnitude of loading applied on the ridge, the technique of extraction and the healing potential of the patient seem to affect this.

The edentulous ridge can be classified according to the amount of bone in both the vertical and horizontal axes:

- Class I: dentate

- Class II: immediately post-extraction

- Class III: well-rounded ridge form, adequate in height and width

- Class IV: knife-edge ridge form, adequate in height and inadequate in width

- Class V: flat ridge form, inadequate in height and width

- Class VI: depressed ridge form, with some basal loss

Alveolar bone resorption is an important consideration when designing complete dentures. In the absence of natural dentition, such dentures are relying completely on soft tissues for their support. As a consequence, the forces exerted on the mucosa are significant and may, in turn, lead to an increased rate of bone resorption. Therefore, in order to ensure an equal distribution of forces across the mucosa, complete dentures should have maximum extensions.

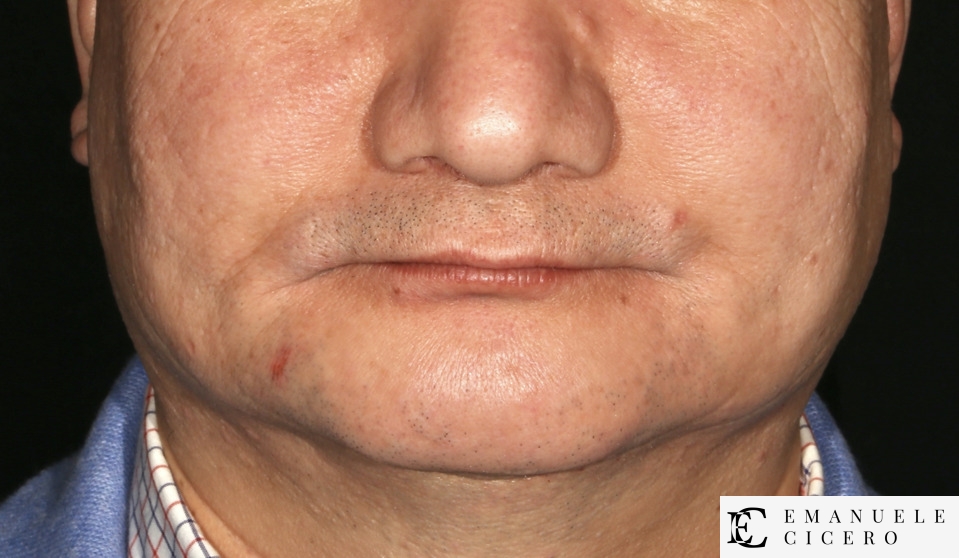

Facial muscles on the cheeks and lips also lose their support as teeth are lost, contributing to an ‘aged’ appearance of the individual. Although complete dentures cannot prevent the loss in muscular tone (as they are not firmly attached to the skeletal system), they can nevertheless provide some artificial support to mask this loss in tone. Furthermore, perhaps the most noticeable effect of tooth loss from a patient perspective is the loss in masticatory (or chewing) efficiency. Teeth function to help with the chewing of food, breaking it down into small pieces that can be swallowed. Denture wearing can bring some masticatory function back to normal.

It cannot, however, fully compensate for the efficiency of the natural dentition because (1) dentures are not fixed in place like teeth are and so have to be actively.

Principles of complete dentures

Complete dentures are prone to a variety of displacing forces of differing magnitude as they are resting on the oral mucosa and are in close proximity with tissues that are constantly changing due to the action of muscles. Consequently, for complete dentures to be retentive and stable, the retentive forces that hold the dentures in place must be greater than the ones aiming to displace them. Obtaining maximum stability and retention is one of the biggest challenges in full denture construction.